The UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme

Report, December 2025

Foreword

“We urge our government and the European Union to show ambition, flexibility and trust and to rise to this moment of possibility together.”

When I wrote these words in April 2025 to the Minister for European Relations, Nick Thomas-Symonds, it was to urge our government and European partners to back calls from MPs for a youth mobility scheme ahead of the UK-EU Summit, held in London that month.

The summit was an undoubted success. It demonstrated that trust is being rebuilt and delivered the commitment in principle to a youth experience deal. Just over six months on, now is the time to focus minds on policy detail and delivering a substantial agreement.

This report, from the cross-party, cross-industry UK Trade and Business Commission (UKTBC) delivers 17 substantive recommendations for the UK Government, and our EU partners on how we can make a youth experience scheme a reality.

This report was compiled following expert witness sessions, and invaluable input from our UKTBC Members, who combine decades of experience across politics, business, diplomacy, trade and the law. As Chair, it’s my privilege to be able to call on their experience and to thank them for such a robust report.

The UK Trade and Business Commission is agreed that, designed appropriately, a youth experience scheme would provide 18-30-year-old Brits and Europeans economic, educational and cultural opportunities. Moreover, it can be a key component of the new and improved partnership with our European neighbours: a win-win for both partners.

This document details our proposal to unlock a deal. It proposes a capped and time limited youth experience scheme. It respects the government’s manifesto commitments and stated red lines, but it is ambitious for the future and unashamedly talks about how the numbers of 18-30-year-olds benefitting from a future scheme could grow over time. It also makes clear that careful work must be done to ensure that a youth experience is an affordable and inviting proposition for young people from all backgrounds – not just those with access to family wealth or savings.

It's not so long ago that a UK Prime Minister was unable to answer whether France was our ally. We have come a long way since the nadir in the UK and European relationship, but now is the time to capitalise on all the diplomatic success of the last year and make a youth experience scheme one of the signature achievements of a renewed UK/EU relationship.

Rt Hon Andrew Lewin MP

Chair

UK Trade & Business Commission

Tom Brufatto

Executive Director of Policy and Research

Best for Britain

James Coldwell

Senior Manager, External Affairs

Best for Britain

Ayesha Chaudhry

Policy and External Affairs Officer

Best for Britain

The UK Government and EU Commission made great strides towards improving the UK-EU relations at the UK-EU Summit in May 2025. Among new pledges on energy, food standards and defence cooperation, negotiators also laid the groundwork for a Youth Experience Scheme, a policy designed to reconnect young people in Europe and the UK and signal a new era of partnership.

In practice, the scheme will provide huge opportunities for young people in both the UK and EU, allowing future applicants to live, work and study in either country for a limited period of time. In the UK however, the Youth Experience Scheme negotiations will span a number of domestically sensitive policy areas.

While the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes have been reducing net migration to the UK in recent years, migration flows are notoriously difficult to predict. Both agreement on a cap in numbers, and details of the deal will define whether the scheme is a policy success for future beneficiaries, and a political success for the UK Government.

Agreement on the maximum duration of stay will be equally important, and the debate is likely to suffer from the same tensions as the arguments around the cap in numbers. The EU is pushing for the longest duration possible - citing four years as an example - when most of France's and Germany’s existing schemes are limited to one year.

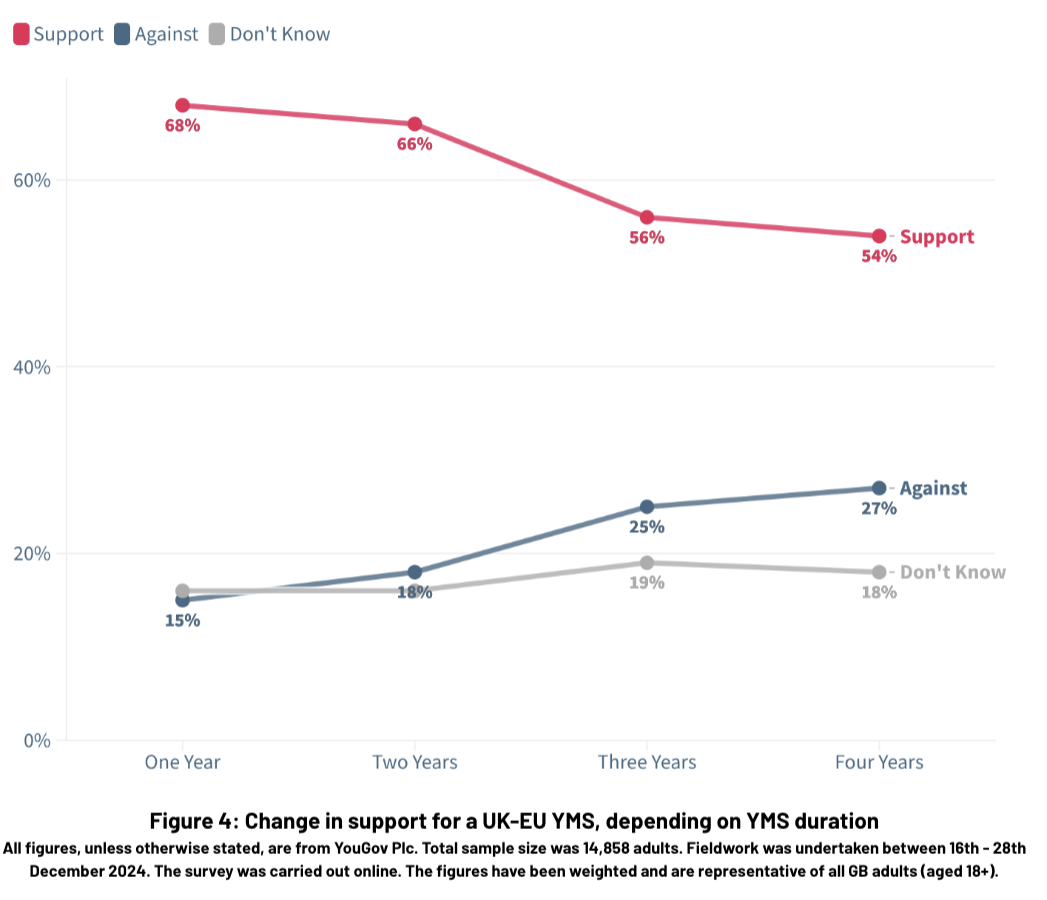

In the UK, despite polling consistently well in principle (60% and above), support for the youth experience scheme drops by 10% if the scheme lasts longer than two years. Though support remains above 50% even for a four-year scheme, polling suggests that a scheme lasting longer than two years could come at the expense of the support of some key voter groups in the UK electorate.

Furthermore, the Youth Experience Scheme cannot be considered in isolation to university tuition fees, and its impact on the UK’s struggling higher education sector more broadly. A scheme which allows EU students to be charged home fees, as is the EU’s ambition, would likely reverse the dwindling numbers of EU students studying in the UK. At the same time, it could exacerbate the financial struggles of some universities, or displace some British students.

Continuing to charge EU students international fees, as has been the case since Brexit, would avoid setting new precedents at a time when the UK Government is negotiating with multiple trade partners, and might improve the finances of a number of struggling UK universities. On the other hand, prohibitive tuition fees will continue the downward trend in EU students coming to the UK, further reducing the UK’s soft power and standing on the world stage - especially with eastern EU member states.

The UK’s reassociation to Erasmus+ will broaden the horizons and opportunities of many young Brits and will help reverse the sharp decline in the number of European students at UK universities. At a time when the UK’s public purse is under significant strain, the size of the financial contributions the UK will need to agree to could reduce the scope of the UK’s participation significantly.

Forthcoming negotiations on eligibility criteria will also be of huge consequence to the scheme's impact on net migration, and how widely the opportunities are spread across the UK. Under current measures, the total financial requirements placed on participants in UK and EU member state youth mobility schemes can exceed £3,000 in either direction - far beyond the means of the many young people in the UK.

Higher application fees, savings requirements and health insurance policies will act as a disincentive to prospective applicants, reducing the scheme’s contribution to the UK’s and EU’s immigration figures. At the same time, higher financial requirements will lock young people from lower income backgrounds out of the scheme. The UK Government and EU will have to balance competing priorities, and make difficult compromises, to ensure the scheme doesn't end up being the preserve of the privileged.

The devolved administrations in Scotland and Wales have each articulated their support for a Youth Experience Scheme between the UK and European Union, underlining the importance of international opportunities for young people and the broader social, cultural, and economic benefits such a scheme would bring.

The Scottish Government advocates for a comprehensive scheme to rebuild the people-to-people links lost after Brexit. The Scottish Government reiterates the necessary flexibility of the youth mobility visa route, and that this must be preserved in any future UK-EU agreement.

The Welsh Government emphasises the need for equitable access for Welsh young people, and for devolved engagement in youth mobility negotiations “to ensure the scheme delivers meaningful benefits for Wales and across the EU”.

All in all, the UK Government will have to assess the benefits and drawbacks of each EU proposal in isolation and in combination to understand the implications of the package as a whole. It will also have to balance any decisions on the welcome commitment to a Youth Experience Scheme in the context of parallel negotiations on food and drink regulations, energy security, and defence cooperation with the EU, while balancing the headwinds of the UK’s domestic politics.

This is a tall order, but seizing the good will on both sides of the Channel, the successful negotiation of a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme will sow the seeds of a new chapter in UK-EU relations, with future generations of British and EU citizens reaping the benefits for generations to come.

Overview

Highlights include:

Deciding the number of YES participants

The notion of a ‘cap’ in relation to the UK-EU YES appears in the UK Government’s UK-EU Summit explanatory notes which reference that “ any scheme should be in line with the UK’s existing schemes ” (which are capped) and in numerous Ministerial public statements since the UK-EU Summit.

With the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes reducing net migration to the UK by approximately 44,000 in 2024, this creates the necessary ‘headroom’ for the UK Government to agree to a Youth Experience Scheme with the EU, in line with its manifesto commitment to reduce net migration to the UK.

Even before considering the number of young UK nationals likely to participate in the scheme, if the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme were to result in 44,000 young EU citizens coming to the UK, the reduction of 44,000 already achieved through the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes would mean there would be no increase in net migration to the UK.

Deciding the maximum permissible duration of stay

Across the UK’s 13 current YMS visa paths, the default maximum permissible duration is currently limited to two years. Exceptions include nationals from Australia, Canada and New Zealand, who may extend their YMS visas by an additional year, bringing the total permissible duration of stay to three years.

For the UK Government to ensure public support for the scheme, the safest negotiating position is to agree a scheme with a maximum of two years. This approach would be in keeping with the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes, and would already be more generous than many EU member states’ arrangements.

Deciding on university tuition fees

The UK Government currently has open trade negotiations with the US, Gulf Cooperation Council, Switzerland, Turkey, South Korea, and China. The UK Government trade strategy further outlines the UK Government’s ambition to negotiate Digital Trade Agreements with Brazil, Thailand, Kenya and Malaysia.

Continuing to charge EU students international fees, as is the case now and the case with students from all other countries across the globe, will not set new precedents and not add to the financial woes of UK universities. At the same time however, it would likely continue to drive the downward trend in the number of EU students coming to the UK to obtain a degree, and further reduce the UK’s soft power and standing on the world stage.

Keeping respective UK and EU member state student visa routes separate to the propose non-purpose-bound UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme will therefore create the opportunity to maximise the overall duration of stay in either country.

The UK’s reassociation to ERASMUS+

Negotiations on the UK’s potential association with Erasmus+ are being progressed separately from the Youth Experience Scheme, reflecting their distinct objectives and policy considerations.

The UK Government should ensure that any financial contribution to the Erasmus+ programme is proportionate to the level of participation by British students and institutions. The UK’s contribution should be tailored to reflect the number of UK participants and the value of opportunities received, ensuring that the benefits to the UK are commensurate with its financial input.

Deciding the scheme’s financial requirements

For the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme to succeed, it must be genuinely accessible to young people across the UK and Europe. While the scheme’s overall participation will be managed through a strict cap on numbers, financial barriers remain one of the most significant hurdles for applicants. Young people from modest backgrounds, eager to study or work abroad, should not be deterred by fees or overly restrictive savings requirements.

Application fees, for example, should be reduced to as close to a nominal level as possible, signalling that the UK Government prioritises participation. Health coverage should also be simplified. The UK Government should manage access to health services through the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) for entrants to the UK, removing the need for the standard health surcharge. Conversely, UK citizens participating in the scheme in EU member states should be able to access the host country’s health services through the UK Global Health Insurance Card. This approach ensures simplicity for participants on both sides of the Channel.

Savings and proof of income requirements are likely to be the main barrier to young UK citizens from modest backgrounds seeking to participate in the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme. To address this, the UK Government should explore the possibility of setting up a scheme for young UK applicants who are unable to meet any agreed savings requirements.

Recommendations

Contents

1. Deciding the number of YES participants

The first major decision facing the UK Government will be deciding the ‘cap in numbers’ - the number of Youth Experience Scheme (YES) visas to be issued each year. The Common Understanding makes no reference to a cap or quota, and instead only references that the proposed YES should be “ balanced ”, and “ensure that the overall number of participants is acceptable to both sides”.

The notion of a ‘cap’ in relation to the UK-EU YES appears in the UK Government’s UK-EU Summit explanatory notes which reference that "any scheme should be in line with the UK’s existing scheme ” (which are capped) and in numerous Ministerial public statements since the UK-EU Summit.

Conversely, the EU negotiating mandate published ahead of the 19 May UK-EU Summit states clearly that “The envisaged agreement on youth mobility should be guided by the following parameters: [...] Mobility is not subject to quota”. Although the EU has since accepted the need for any scheme to be capped, the substantially different approach to the cap suggests there may yet be disagreements between the UK Government and the EU on what constitutes an acceptable cap in numbers.

1.1 The salience of migration in the UK

The UK Government was elected with an explicit manifesto commitment to “reduce net migration” to the UK, and since the 2024 General Election, migration has only increased in public salience.

From the recent White Paper, “Restoring Control over the Immigration System”, published in May 2025, the UK Government’s stated priority is to bring down net migration through an immigration system that is properly managed, controlled and fair . The UK Government has set out a series of reforms designed to reduce overall migration levels while ensuring that immigration continues to meet the needs of the economy. This includes tightening visa eligibility criteria, raising salary thresholds for skilled workers and reviewing routes that contribute significantly to net migration. Although immigration remains a salient public issue, the latest figures published by the Office for National Statistics on 27 November 2025 show that net migration to the UK is already falling rapidly.

Recent Best for Britain public opinion polling suggests that in September 2025, immigration and asylum was the second most important issue facing the UK, after the cost of living. Best for Britain’s research concluded that concerns about immigration and asylum were overwhelmingly shaped by perceptions of ‘illegal’ immigration rather than ‘legal’ immigration, and driven by political and media discourse as opposed to first-hand experiences.

At the same time, public opinion polling on the popularity of a YMS remains encouraging for policymakers.

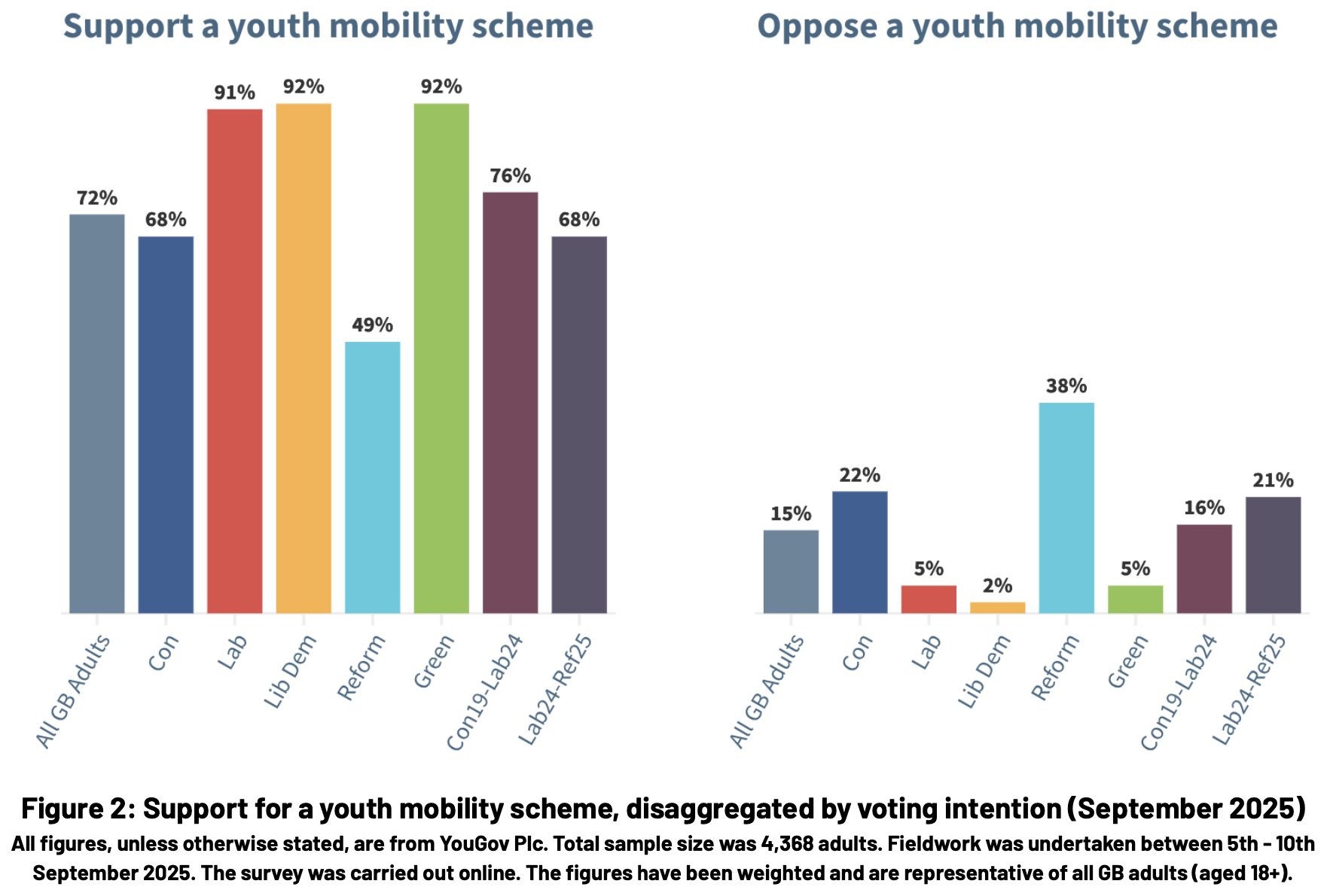

In September 2025, more than seven in ten survey respondents (72%) expressed their support for a UK-EU Youth Mobility Scheme, nearly five times the proportion of those who opposed it (15%).

Figure 2 illustrates the extent of cross-party support for a UK-EU YMS. Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the Green Party supporters demonstrate near-unanimous levels of endorsement, with more than nine in ten supporters for each of these parties being in favour of a YMS.

Notably, support also remains substantial among Conservative and Reform UK voters, with more than two in three (68%) Conservative supporters and approximately half (49%) of Reform UK supporters endorsing the Government’s policy of establishing a YMS with the EU.

With regard to the evolving composition of voting coalitions and electoral preferences, the UK Government can take particular confidence from the views of two strategically significant groups. First, voters who switched from the Conservative Party to Labour at the last general election demonstrate higher-than-average support for a YMS, with more than three in four (76%) within this cohort expressing approval.

Even among those who voted Labour in the previous election but now lean towards Reform UK, support for a YMS remains high. More than two-thirds (68%) of these voters are supportive, with only 21% opposed to the scheme.

Public opinion polling has consistently demonstrated strong public support for the Scheme. Best for Britain polled the proposed YMS in May 2023, March 2024, December 2024 and May 2025.

The latest Best for Britain polling carried out in September 2025, shows that support for the UK-EU YES has grown since the UK-EU Summit. The consistent popularity of the proposed YMS is shown in Figure 3.

The UK Government clearly has the political and policy space to negotiate a Youth Experience Scheme with the EU. The challenge facing the UK Government is therefore limited to ensuring that any such scheme is consistent with its manifesto commitment and stated ambition to reduce net migration.

1.2 Comparable YES precedents in the UK

The UK Government currently operates Youth Mobility Schemes with 13 countries, including Australia,Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Iceland, Uruguay, Hong Kong and Taiwan. These bilateral agreements offer young people aged 18–30 (or 18–35 for some nationalities) the opportunity to live and work in the UK for up to two or three years, providing valuable cultural exchange and personal development.

The quotas of the UK’s 13 existing Youth Mobility Visa (YMS) Schemes vary significantly and are allocated every year, as detailed in Table 1.

When it comes to the UK’s existing YMS schemes, it is clear that they have been reducing net migration to the UK.

In 2024, the UK granted 24,400 21 YMS visas, under a third (30%) of the total number of visas available across all UK YMSs. Over the same period, 68,495 22 UK citizens are estimated to have emigrated to Australia, New Zealand and Canada under the UK’s YMS visa programmes.

Without accounting for the number of UK citizens moving abroad as part of the UK’s remaining 10 YMS programmes, the UK’s YMS programme had an effect of reducing net migration to the UK by over 44,000 in 2024.

This pattern was repeated the year before, in 2023, when 23,000 people came to the UK in all the UK’s YMS schemes. During the same period, 34,000 UK citizens left the UK for Australia and New Zealand alone. Predicting migration flows is however notoriously difficult, and the relative popularity of a UK-EU YES among eligible UK and EU citizens will be equally complicated to predict. Push and pull factors will vary nation to nation and the level of agreed financial disincentives will also have a significant impact on the number of applicants.

The UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes are therefore creating ‘headroom’ for the UK Government to negotiate a Youth Experience Scheme with the EU, while also meeting its manifesto commitment to reduce net migration to the UK. In 2024 this ‘headroom’ amounted to over 44,000 visas, before taking into account the number of young UK nationals likely to participate in the Youth Experience Scheme with the EU.

1.3 Comparable precedents in EU Member States

Although the proposed EU-wide UK-EU YES scheme will be the first of its kind for the EU, member states have numerous bilateral YMS schemes (often called “working holiday” schemes) in place with third countries. For example, both Germany and France have bilateral schemes in place with Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, South Korea, Japan, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Uruguay. France has additional schemes with Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico and Peru. Germany has an additional bilateral scheme with Israel.

Although information is not always readily available, it is clear that many of France’s and some of Germany’s working holiday visa programmes are also subject to annual quotas. France’s working holiday visa programmes include both capped and uncapped schemes, depending on the country. France’s working holiday programmes with Australia and New Zealand are uncapped. The caps of each of France’s remaining working holiday programmes are listed in Table 2.

Details of Germany’s annual working holiday quotas are harder to come by, although Germany appears to issue a capped number of annual visas for Brazil (1,000 visas), Hong Kong (300 visas) and Taiwan (500 visas). Canada’s working holiday application website suggests that there may be a quota of 3,490 visas for Canadians wishing to live in Germany for the 2025 season.

1.4 Policy Recommendations

Migration remains one of the most politically sensitive issues in British politics. Against this backdrop, the UK Government should approach negotiations over a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme carefully. While polling shows strong public support for the scheme in principle, any perception that the scheme could drive up migration figures could risk turning an otherwise popular policy into a political liability.

A clear cap on numbers, with annual reviews built in, provides the reassurance the public expects. Such an approach would mirror the design of the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes, as well as schemes run by many EU member states.

Recommendation [1]

In line with existing UK Youth Mobility Schemes, and many EU member state schemes, the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme should be subject to an annual cap in numbers of participants, to ensure the policy commands the support of the British public.

An example of how the cap can be deployed in practice can be found by looking at the existing UK-Australia Youth Mobility Scheme. The annual definition of the cap in numbers of the reciprocal UK-Australia Youth Mobility Scheme has proved to be flexible, allowing numbers to be adjusted year by year. In 2025, our youth mobility scheme with Australia was capped in both directions at 42,000 places, whereas in 2024 the cap sat at 45,000 places.

The agreement on the cap in numbers should be accompanied by a commitment to review the number of available visas on an annual basis. This commitment would be in line with both the UK and EU member states’ existing schemes, which allocate the cap of available visas on an annual basis.

Recommendation [2]

In line with existing UK schemes, and many EU member state schemes, the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme cap on the number of participants should be reviewed and agreed annually. It will be for the EU Commission to decide how participant numbers are allocated between EU Member States. This allocation process should not form part of the UK-EU agreement.

As part of the EU’s negotiation mandate for the proposed UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme, the EU Commission proposed that, in line with many other elements of the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement, implementation of the Youth Experience Scheme should be overseen by a new specialised committee.

Recommendation [3]

The UK Government and the EU should agree to the creation of a specialised committee to oversee the implementation of the new UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme. As part of the specialised committee’s remit, it should monitor uptake from both UK and EU nationals and make recommendations to the UK Government and the EU Commission on the annual cap on numbers of participants.

The UK Government and EU Commission should be meticulous in gathering and sharing data on uptake, implementation and delivery of all aspects of the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme.

Recommendation [4]

The UK Government and EU Commission should be meticulous in gathering data on uptake, implementation and delivery of all aspects of the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme. All data concerning the scheme should be made available to the new UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme specialised committee, to ensure it is able to make educated recommendations on the annual cap on the number of participants in a timely fashion.

The Migration Advisory Committee reported that in 2024 the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes reduced net migration by approximately 44,000.

This finding creates the headroom for the UK Government to agree to a Youth Experience Scheme with the EU, whilst honouring its manifesto commitment to reduce net migration to the UK. It would allow UK Ministers to guarantee that, taken together, Youth Mobility and Youth Experience schemes will have at most a net-neutral effect on the UK’s net migration figures.

The UK Government should therefore consider the impact of the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes and UK–EU Youth Experience Scheme on net migration to the UK in aggregate rather than in isolation.

Recommendation [5]

The UK Government should consider the impact of the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes and UK–EU Youth Experience Scheme on net migration to the UK in aggregate, rather than in isolation. With the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes reducing net migration to the UK by approximately 44,000 in 2024, this creates the necessary ‘headroom’ for the UK Government to agree to a Youth Experience Scheme with the EU, in line with its manifesto commitment to reduce net migration to the UK.

Even before considering the number of young UK nationals likely to participate in the scheme, if the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme were to result in 44,000 young EU citizens coming to the UK, the reduction of 44,000 already achieved through the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes would mean there would be no increase in net migration to the UK.

A pragmatic UK Government position would be to propose a scheme that is capped at 44,000 visas for the first year of the scheme’s duration, coupled with the aforementioned built-in review mechanism and clear commitment to annual reviews of the cap. If demand proves high, the cap could be raised in line with evidence of the scheme's implementation.

The Scottish Government has outlined its in-principle support for a capped scheme, provided that any quota cap is set at a level that does not unduly constrain participation and is subject to regular review informed by evidence. The Welsh Government has not made explicit reference to quotas but has welcomed “the UK and EU’s announcement of a mutual commitment to negotiate a youth mobility scheme”.

Ultimately, the caps will define how the Youth Experience Scheme is sold to the public. By presenting the scheme as capped, reviewed, and offset within the broader migration system, the UK Government can claim that it is both delivering new opportunities for young people and delivering on its manifesto commitment and stated ambition to reduce net migration to the UK.

Recommendation [6]

The UK Government should use the headroom provided by the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes to agree that the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme should be capped at 44,000 participants on each side for the first year of the scheme.

This would allow the UK Government to agree to the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme in full confidence that the UK’s youth schemes will have at most a net-neutral impact on the UK’s net migration figures. This cap should act as a floor rather than a ceiling.

Based on the sizes of the UK’s 2025-2026 Youth Mobility Schemes, a cap of 44,000 visas would make the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme the most generous of all the UK’s existing youth schemes.

Estimating the number of UK nationals likely to participate in the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme, without a precedent, is not without complications. Professor Brian Bell, Chair of the Migration Advisory Committee, told the UK Trade and Business Commission it was possible 50,000 UK nationals would travel to the EU on the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme.

“Suppose we had a scheme that was capped, and it was capped at, say, 50,000 people a year. [...] So, if we had 50,000, could I imagine 50,000 Brits going to Europe every year? Yeah, absolutely. I think that would be a reasonable thing to assume.”

- Brian Bell, Chair of the Migration Advisory Committee and Professor of Economics at King’s Business School

After the first year of the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme’s implementation, and with full knowledge of the balance of uptake by both UK and EU nationals, the UK Government and EU can review and increase the annual cap in numbers. With the knowledge of the number of UK participants in the scheme, the UK Government can recalculate the new headroom provided by all the UK’s youth schemes, ensuring that the cap in numbers of participants for the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme is maximised, in line with the UK Government’s stated ambition to reduce net migration to the UK.

Recommendation [7]

After the first year of the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme, the UK Government should combine the number of UK nationals participating in the scheme with the headroom provided by all the other UK’s youth schemes to adjust the cap in numbers for the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme accordingly.

The annual review of the scheme will give future UK Governments and the EU Commission the flexibility to increase or decrease the cap in annual number of participants in accordance with their political priorities.

Agreeing to an annual cap in numbers which accounts for both the number of UK nationals participating in the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme, as well as the headroom provided by the UK’s other Youth Mobility Schemes, will allow for maximum participation in the UK-EU scheme, within the bounds of the UK Government's objective of reducing net migration to the UK.

The above process will allow for the impact of the Scheme on net migration to be at most zero, both in the short and in the long term.

“And the only effect you ever have [...] is that some people will be able to switch visas after they finish the Youth Mobility Scheme onto other visas and stay in the long term. [...] But, of course, that will also be applying to the Brits who go abroad. And so, entirely possible that they just have the same probability of staying abroad as we do.

“And you know, people forget the Brits count in the net migration statistics. So, if it's a balanced scheme, my guess is the overall effect on net migration is essentially zero, essentially all the time, and so it's not worth worrying about.“

- Brian Bell, Chair of the Migration Advisory Committee and Professor of Economics at King’s Business School

2. Deciding the maximum permissible duration of stay

The UK Government and the EU Commission will need to agree on the maximum permissible duration of stay under the future UK–EU Youth Experience Scheme (YES). The Common Understanding simply states that the future UK-EU YES should apply “for a limited period of time”, without specifying a precise duration.

The UK Government's explanatory notes reiterate that the scheme will be “time limited” in-line with the structure and parameters of the “UK’s existing schemes”.

On the other hand, the EU’s negotiating mandate takes a more defined position, stating that the envisaged YES should be “...guided by the following parameters: [...] The period of stay is limited to a reasonable timeframe (e.g. 4 years)”. The mandate also notes that existing UK visa pathways are ‘limited’ including due

to their relatively “short time limitations”.

Taken together, these documents indicate a shared expectation that the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme will be of finite duration, though the specific period of stay remains subject to negotiation between the parties

2.1 The UK’s and EU member states’ precedents

Across the UK’s 13 current YMS visa paths, the default maximum permissible duration is currently limited to two years. Exceptions include nationals from Australia, Canada and New Zealand, who may extend their YMS visas by an additional year, bringing the total permissible duration of stay to three years.

By comparison, France’s bilateral working holiday visa paths allow a maximum stay of one year, with no extensions, except for the France-Canada scheme, which permits a one-year renewal. Germany’s working holiday programmes are similarly limited to one year stays, with Canada again the only exception, allowing Canadian participants to apply for a second working holiday visa, extending their duration of stay by one year only.

When it comes to the maximum permissible duration of stay, the UK’s current Youth Mobility Schemes are more generous than the equivalent schemes in EU member states.

2.2 Public opinion in the UK

In its role as secretariat to the UK Trade and Business Commission, Best for Britain has monitored support for a UK-EU Youth Mobility Scheme since the UK Trade and Business Commission proposed the measure in May 2023.

In December of 2024, Best for Britain commissioned a Multilevel Regression and Post-Stratification (MRP) poll of 15,000 respondents exploring how support for a YMS changed with YMS duration. As shown in Figure 4, the study found that support for a UK-EU YMS varied with the duration of stay.

2.3 Policy Recommendations

While the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme is widely popular in principle, any perception that young people could remain in the UK for too long, risks provoking public concern over migration.

For the UK Government to ensure public support for the scheme, the safest negotiating position is to agree a scheme with a maximum of two years. This approach would be in keeping with the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes, and would already be more generous than many EU member states’ arrangements.

Recommendation [8]

In line with existing UK Youth Mobility Schemes, the UK Government and EU Commission should agree to a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme with a baseline duration of two years, ensuring the scheme commands broad-based public support in the UK.

Furthermore, the UK Government should approach negotiations with flexibility and agree to a possible one year extension. This structure would safeguard public support and be in line with the precedents set by the UK’s Youth Mobility Schemes with Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and extensions available in French and German Working Holiday Visa schemes with Canada.

Recommendation [9]

In line with existing UK Youth Mobility Schemes, the UK Government and the EU Commission should agree to include the option to extend a participant’s duration of stay by one year. Although only a minority of participants are likely to choose to extend their stay, this provision will bring the maximum duration of the scheme to three years.

The study found that, in aggregate, two thirds of respondents supported UK-EU YMS schemes lasting one (68%) and two (66%) years, with fewer than one in five opposed (15% and 18% respectively).

The survey also found that for schemes lasting longer than two years, support dropped by at least 10 percentage points. While a majority continued to support a UK-EU YMS of any duration, support for a three year YMS was supported by 56% while a four year YMS was supported by 54% of respondents.

The MRP modelling found that in aggregate, people in every constituency in Britain were more likely to support a Youth Mobility Scheme of any duration than oppose it.

Support for a two-year scheme was driven by Labour (81%) and Liberal Democrat (84%) supporters. The reduction in backing for longer YMS durations was found to be driven primarily by Reform UK supporters.

A two-year scheme carried majority support among Conservatives (57% in favour) and Conservative to Labour Switchers (67% in favour), though Reform UK supporters were divided (40% in favour, 46% against).

In contrast, a four-year YMS faced clear opposition from Reform UK supporters (59% against) and divided Conservatives (44% against, 40% in favour), as well as Conservative to Labour Switchers (39% against, 49% in favour). These findings indicated that a two-year scheme commanded the broadest political support.

As reported in Figure 2, support for a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme has increased since the MRP of December 2024. Despite the increase in public support for a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme since the 19 May UK-EU Summit, a two-year reciprocal UK-EU YES will continue to command broader public support than schemes of a longer duration.

When it comes to the maximum permissible duration of stay, a two-year Youth Experience Schemes is likely to command the broadest support from across the political spectrum.

3. Deciding on university tuition fees

For the UK Government, the YES is designed as a cultural and professional exchange programme, providing opportunities for young people to live, work and travel.

The UK Government views the YES as separate to the existing and dedicated UK student visa path.

The focus on university tuition fees included in the EU’s negotiation mandate indicates a clear difference in how the UK and the EU perceive the purpose of the proposed UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme.

The EU’s negotiation mandate instead clearly states that the UK-EU YES should provide a “clear, simple and cost-effective path for mobility” which would also “address the main hurdles for young Union citizens (e.g. in respect of education tuition fees or of work placements as part of Union studies) which other options (such as the United Kingdom Youth Mobility Scheme) do not address”.

Furthermore, the mandate specifies that the EU is seeking that “equal treatment is also provided in respect of tuition fees for higher education”, meaning that EU citizens participating in the scheme should be charged the domestic rate of tuition fees. If granted, this would constitute a unique concession to EU students. Furthermore, the EU is seeking that this exception be applied to “beneficiaries of other visa paths”, indicating their ambition that any agreement on tuition fees agreed as part of the YES negotiations be extended to EU citizens studying in the UK under the UK’s student visa scheme.

The EU however appears to view the proposed YES as a broader mobility mechanism, functioning as a route for EU students to access UK higher education institutions. Taken at face value, the EU’s mandate would create two parallel visa paths for EU students wishing to study at UK universities: one through the existing UK student visa path and an additional route through the YES programme.

It is likely that the EU demand for EU students being eligible for home fees in the UK is borne from both the uncapped nature of international tuition fees in the UK, and the significantly higher tuition fees in the UK compared to EU member states, where higher education is subsidised. In France for example, domestic undergraduate tuition fees at a public university are around €170/year and €2,770/year for international students (tuition is however comparable for some of France’s grand écoles, which can charge around £9,000). In Germany, tuition is free for both domestic and international undergraduates with the exception of the Baden-Wuttenberg area.

Furthermore, on 20 October 2025 the UK Government announced its “Post-16 Education and Skills White Paper”, confirming that university tuition fees in England will now rise annually in line with inflation, meaning the current cap of £9,535 will increase each year, from 2026 onwards. The policy is intended to provide long-term certainty over future funding for the higher education sector, and the UK Government also intends to “legislate when parliamentary time allows to increase tuition fee caps automatically for future academic years”.

The proposed increase in tuition fees for England does not affect fees in Scotland and Northern Ireland, where fees are already significantly lower than in England and Wales. The Welsh Government is yet to make an announcement on tuition in Wales. This poses an additional complication in the interpretation of the EU’s demand for ‘equal treatment to nationals’. Taken at face value, and based on 2025 tuition fees, this could result in future EU undergraduate students being charged the lower £1,820 home fees for Scottish citizens in Scottish universities43 and £4,855 in universities in Northern Ireland, with English and Welsh citizens paying the higher ‘Rest of the UK’ fees, currently capped at £9,535/year, rising in line with inflation in future.

In its April 2025 policy position paper, Youth Mobility Agreement with the EU, the Scottish Government notes that previous EU proposals in this area have addressed the fee-paying status of EU students who might come to the UK under such an agreement. The paper further emphasises that any approach must carefully consider Scotland’s distinct funding arrangements, the perspectives of higher education institutions, and the need to avoid creating a “funding gap” that could negatively impact Scottish universities”.

In 2021, when the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) came into effect, applications from EU students to UK universities dropped by 40%. Although the TCA’s implementation coincided with the lockdowns and travel restrictions resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, in 2024, the number of EU students on full-time undergraduate courses had fallen by 68% compared to 2020 - its “lowest level since 1994”. Despite the compounding effects of Covid-19 pandemic, it is clear that higher tuition fees caused the number of EU students in the UK to crash, and they have so far not recovered.

In September 2024, the Chief Executive of Universities UK, Vivienne Stern called on the new UK Government to seek to increase the flow of EU students to the UK, saying: “We really, really regret the fact that we have lost a flow of really good European students into the UK”. She also recognised the “toxic” domestic politics surrounding the prospect of EU citizens returning at scale to education in the UK.

When it comes to the type of degree EU students are obtaining in the UK, EU students are outliers compared to non-EU international students. For the 2023/2024 academic year, 63% of EU students at UK universities were in first-time undergraduate courses, compared to only 35% of non-EU international students who were doing the same.

It is therefore possible that a reversion to charging EU students UK home fees, as was the case before the TCA was implemented, could help the number of applications from EU students in the UK to recover. However, before the UK Government announced that tuition fees in England would rise in line with inflation from 2026 onwards, universities were concerned that charging EU students domestic tuition fees could accelerate the financial crisis of UK universities or result in EU students “displacing British students”.

“The main thing to be aware of here is just that we're in a very precarious situation in terms of Higher Education funding at the moment. [...] I think expanding home fee status to include European students would really greatly exacerbate this problem.”

- Charley Robinson, Head of Global Mobility Policy at Universities UK

The first consideration for the UK Government is whether to set a new precedent by allowing EU citizens to pay home fees, and how such a precedent may impact both on all other current international students in the UK and ongoing and future trade negotiations.

“A very real question for us is about parity with international students and on what basis we could grant preferential access and how that would go down with other international students, who are really the lifeblood of the existing Higher Education funding system.”

- Charley Robinson, Head of Global Mobility Policy at Universities UK

The UK Government currently has open trade negotiations with the US, Gulf Cooperation Council, Switzerland, Turkey, South Korea, and China. The UK Government trade strategy further outlines the UK Government’s ambition to negotiate Digital Trade Agreements with Brazil, Thailand, Kenya and Malaysia.

Continuing to charge EU students international fees, as is the case now and the case with students from all other countries across the globe, will not set new precedents and not add to the financial woes of UK universities. At the same time however, it would likely continue to drive the downward trend in the number of EU students coming to the UK to obtain a degree, and further reduce the UK’s soft power and standing on the world stage.

“There is a big soft power dimension to this for us, which is if there are people who are the future business leaders of multinational corporations overseas who have come and had a positive experience of the UK, there is a soft power element to that.”

- Matthew Percival, Director, Future of Work and Skills, Confederation of British Industry

A UK-EU YES which agrees to allow EU students to be charged home or reduced international fees would bring the welcome benefit of reversing the downward trend in the number of EU students choosing to come to study in the UK.

The UK Government will have to balance these competing priorities, ensuring that any YES agreement supports youth mobility and cultural exchange without undermining the financial resilience of UK universities or compromising the UK’s broader trade policy objectives.

3.1 The impact of tuition fees on UK universities and EU students

However, under the UK’s dedicated student visa path, a typical EU citizen seeking to complete afirst-time undergraduate course at a UK university can stay in the UK for up to five years.

Both the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes, and EU member state Working Holiday Visa schemes include a ‘once in lifetime’ limitation, meaning that participants can only use this visa route once.

Keeping respective UK and EU member state student visa routes separate to the proposed non-purpose-bound UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme will therefore create the opportunity to maximise the overall duration of stay in either country.

“The existing YMS schemes are a good template in that respect. I think it's really important that it's a visa route, it’s a straightforward application to the Home Office and applications to study are an entirely separate and independent process. We'd want to keep it that way. I think the existing route's flexibility, as others have said, is really, really important.”

- Charley Robinson, Head of Global Mobility Policy at Universities UK

Agreeing to the EU’s demand of using the proposed UK-EU YES scheme as an alternative student visa route to access UK universities could therefore result in a reduction in maximum duration of stay for an EU participant, compared to the maximum stay by using the UK student visa route. It would also result in EU participants using up their ‘once in a lifetime’ quota for participation in the UK-EU YES unnecessarily

3.2 Policy Recommendations

Tuition fees for EU students remain a sensitive element of Youth Experience Scheme negotiations. Continuing to charge EU students international fees would avoid setting a new precedent and keep the UK-EU YES scheme in line with UK Government policy for students from the rest of the world. Maintaining international fees is also unlikely to impact on the financial situation of UK Universities, many of which rely on this income to sustain teaching and research.

The UK Government should, however, engage closely with higher education providers, particularly universities facing financial pressure, to explore the implications of allowing EU students to pay ‘home fees’ or reduced international fees. In the event that home fees are introduced for EU students, they should be set at the highest level applied in England and Wales, to prevent EU students from taking advantage of lower tuition in Scotland or Northern Ireland. This ensures consistency and fairness across the UK’s higher education system.

The UK Government should conduct a comprehensive impact assessment to evaluate the financial and operational consequences of charging EU students home fees or reduced international fees, ensuring that any policy decisions are informed by the potential effects on universities and other education providers across the UK.

Recommendation [11]

The UK Government should not accept the EU’s request to charge EU students ‘domestic fees’ but should consider consulting the higher education sector to determine if increasing tuition fees in England in line with inflation creates the possibility of charging EU students ‘domestic fees’ or other concessionary fees in future.

A function of a mature UK-EU relationship is that there will be requests from both sides that cannot be accommodated. This should be regarded as a normal aspect of balanced negotiations.

Recommendation [10]

The UK Government and EU Commission should agree that the proposed UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme should not be purpose-specific, and considered to be separate to existing UK and EU member state student visa paths.

4. The UK's reassociation to ERASMUS+

In the Common Understanding, the UK and EU committed to “work towards the association of the United Kingdom to the European Union Erasmus+ programme”, and this commitment has drawn widespread support.

The details of the terms of association are still under discussion, and are likely to focus on the “fair balance" between the UK’s financial contributions to the scheme, and the “benefits to the United Kingdom”. The UK Government’s explanatory notes go further, detailing that negotiations on Erasmus+ are taking place “on the clear mutual understanding that the UK will only associate to Erasmus+ on significantly improved financial terms”.

“I think in terms of what considerations the Government should consider when thinking about negotiating a fee to rejoin, we're really supportive of the UK rejoining Erasmus, it’s going to provide that critical long-term sustainable funding for students and staff mobility and exchanges. It obviously needs to be fair and a contribution that can be justified in terms of that public perception as well.”

- Charley Robinson, Head of Global Mobility Policy at Universities UK

In 2018, 29,797 EU students came to the UK through Erasmus+, 64% more than the number of UK students going the other way. The value of Erasmus+ projects in the UK in 2018 was €145million (around £127million). For the same time period, Boris Johnson’s government estimated the proportion of the UK’s contribution to the EU budget allocated to Erasmus+ to be £241million.

Negotiations on the UK’s potential association with Erasmus+ are being progressed separately from the Youth Experience Scheme, reflecting their distinct objectives and policy considerations.

The UK Government should ensure that any financial contribution to the Erasmus+ programme is proportionate to the level of participation by British students and institutions. The UK’s contribution should be tailored to reflect the number of UK participants and the value of opportunities received, ensuring that the benefits to the UK are commensurate with its financial input.

Recommendation [12]

The UK should ensure that any financial contribution to the Erasmus+ programme is proportional to the level of participation by British students and institutions. The UK’s contribution should be tailored to reflect the number of UK participants, ensuring that the benefits to the UK are commensurate with its financial input. This process should be considered separate from Youth Experience Scheme negotiations.

5. Deciding the scheme’s financial requirements

Discussions between the UK Government and the EU have established the shared political ambition to launch a UK-EU Youth Exchange Scheme that supports cultural exchange and short term mobility for young people. However, several financial and administrative issues remain unresolved, reflecting differing approaches to visa costs, healthcare access and proof of funds.

Both parties have agreed that the scheme should be reciprocal, capped, and fiscally neutral, meaning participants are expected to cover their own costs without drawing on public funds. The UK Government has made clear in its explanatory notes that any scheme must be consistent with its existing Youth Mobility Scheme framework, including no access to benefits, no dependents, and full cost recovery through visa and healthcare charges.

The EU’s negotiating mandate has stated that: “Fees for handling the applications or issuing a visa or residence permit should not be disproportionate or excessive”.

5.1 Comparison of UK and EU's financial requirements

Under existing UK Youth Mobility Schemes, participants must pay £319 in visa fees, more than three times higher than equivalent schemes in France (€99/£88) and Germany (€75/£65)60. Although this is lower than the UK’s international student visa fees, which currently cost £524, it still represents a significant up-front cost for a short-term, non-settlement visa.

In addition to the visa fee, all UK youth mobility scheme participants must pay an Immigration Health Surcharge (IHS) of £776 per year, granting access to the National Health Service care during their time in the UK. The same surcharge applies to international students residing in the UK on a student visa, although EU students may claim a refund if they hold a valid European Health Insurance Card.

By contrast, EU member states such as France and Germany operate an insurance-based model, requiring applicants to obtain private medical insurance covering up to €30,000 in medical costs. UK citizens participating in equivalent EU schemes can avoid purchasing this insurance, if they possess a UK Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC).

The EU’s negotiating mandate reinforces this approach, stating visa and residence permit fees “should not be disproportionate or excessive” and that any “envisaged agreements should waive, for Union beneficiaries, the United Kingdom healthcare surcharge” while maintaining the requirement for “valid comprehensive sickness insurance”.

Beyond visa and healthcare costs, both systems impose financial eligibility conditions. In the UK, YMS applicants must demonstrate a minimum of £2,530 in savings. In France, the requirement ranges between €1,700-€3,100 (£1,470-£2,680) in savings, depending on the country of origin. Similarly, Germany requires YMS applicants to demonstrate €3,000 (£2,600) in savings and proof of a €1,000 (£866) monthly income.

This level of financial commitment risks making the scheme prohibitively expensive for many young people, particularly those from lower income backgrounds.

If agreed, the combined burden of a £319 visa fee, annual £776 health surcharge and a £2,530 savings requirement may deter applicants and reduce participation. The Scottish Government reiterates this position in its policy paper, stating that “any fees and charges should be proportionate and reflect the actual costs associated with the immigration route”.

“I think on the financial side, there's a cost attached to the visa. I think the current ones are about £331 for the visa application fee, and then there's the immigration health survey charge at, I think, £776. That's not an insubstantial upfront visa cost that students would have to navigate.”

- Charley Robinson, Head of Global Mobility Policy at Universities UK

While these measures are designed to ensure fiscal neutrality and prevent additional pressure on public services, they may unintentionally reduce the inclusivity and accessibility of the programme. Coupled with the “no recourse to public funds” condition and the IHS, the scheme may appear less attractive to those without substantial financial means.

As negotiations progress, careful consideration should be given to balancing financial disincentives with accessibility. Ensuring that the scheme remains equitable, affordable, and reflective of its broader cultural and economic objectives will be essential to its long-term success.

A young person seeking to participate in either the UK’s or EU member states’ existing schemes faces financial requirements of around £3,000 before accommodation, travel, or other living expenses are considered.

5.2 Policy Recommendations

For the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme to succeed, it must be genuinely accessible to young people across the UK and Europe. While the scheme’s overall participation will be managed through a strict cap on numbers, financial barriers remain one of the most significant hurdles for applicants. Young people from modest backgrounds, eager to study or work abroad, should not be deterred by fees or overly restrictive savings requirements.

In evidence given to the UK Trade and Business Commission, stakeholders repeatedly emphasised the importance of making youth mobility schemes financially accessible. To achieve this, the UK Government should seek to minimise the scheme’s financial requirements, while overall participation numbers should be controlled through the agreed cap in numbers.

Application fees, for example, should be reduced to as close to a nominal level as possible, signalling that the UK Government prioritises participation.

Recommendation [13]

The UK Government and EU Commission should aim to reduce application fees for the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme to as close to nominal as possible.

Health coverage should also be simplified. The UK Government should manage access to health services through the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) for entrants to the UK, removing the need for the standard health surcharge. Conversely, UK citizens participating in the scheme in EU member states should be able to access the host country’s health services through the UK Global Health Insurance Card. This approach ensures simplicity for participants on both sides of the Channel.

Recommendation [14]

The UK Government and EU Commission should agree to manage access to healthcare through the mutual recognition of the EU Health Insurance Card and the UK Global Health Insurance Card.

The UK Government should accept the EU’s request to waive the health surcharge.

Savings and proof of income requirements are likely to be the main barrier to young UK citizens from modest backgrounds seeking to participate in the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme. Evidence submitted to the UK Trade and Business Commission highlighted that young people from less affluent backgrounds might be deterred if the scheme demanded high levels of savings upfront

To address this, the UK Government should explore the possibility of setting up a scheme for young UK applicants who are unable to meet any agreed savings requirements.

Recommendation [15]

The UK Government should establish a UK Government scheme ensuring UK citizens who are unable to meet the scheme's savings requirements are able to participate in the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme.

Keeping costs low, simplifying access to healthcare, and offering targeted support would make the scheme more inclusive, maximise participation.

6. Other provisions

The EU’s negotiation mandate seeks an agreement on the “conditions for the exercise of the right to family reunification”, something neither the UK nor EU member states’ existing working holiday visa schemes make provisions for.

The UK Government’s explanatory notes clearly state: “The UK has been clear that any scheme should be in line with the UK’s existing schemes including participants having no access to benefits and no right to bring dependents”. This position is consistent with recent changes to UK visa rules, including the reversal of family reunification rights for international students, as recently as January 2024, and suspending the right to family reunification for asylum seekers, from September 2025.

To provide consistency across the UK’s wider visa policy, and in line with both the UK’s and EU member states’ existing YMS schemes, the UK should avoid setting a new precedent by granting access to benefits or family reunification rights under the UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme

Recommendation [16]

In line with the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes, and broader immigration policy, the UK Government should not accept the EU’s proposals for family reunification rights.

On mobility within the EU for UK citizens, it is unclear who will be responsible for the administration and admission of UK YES applicants on the EU side. The proposal is for an EU bloc-wide Youth Experience Scheme, though ‘residence’ will likely be bound to a specific EU member state. The EU’s mandate also stipulates that any future UK-EU YES agreement should “not allow for “intra-Union” mobility to another Member State”, meaning that future UK YES applicants would be able to reside in only one EU country for the duration of their visa.

While this position is expressed ‘without prejudice’ to the Article 21 of the Convention implementing the Schengen Agreement of 14 June 198578, allowing short term travel across the Schengen area, it does not extend to work or residence rights in other Member States.

Recommendation [17]

The UK Government should ensure that UK nationals who are already residing in an EU Member State under the UK–EU Youth Experience Scheme can still make use of the Schengen ‘90 days in any 180-day period’ visa rules.

UK Trade and Business Commission: Panel Sessions

MATTHEW PERCIVAL, Director, Future of Work and Skills, Confederation of British Industry

BRIAN BELL, Chair of the Migration Advisory Committee and Professor of Economics, King’s Business School

CHARLEY ROBINSON, Head of Global Mobility Policy, Universities UK

Shaping the Future: UK–EU Youth Experience Scheme

13th October 2025