On the Youth Experience Scheme

The choices and compromises faced by UK and EU legislators seeking to agree a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme are likely to determine the overall shape of the new UK-EU Strategic Partnership, given that this is a top EU priority. This paper explores the possibilities and limitations, precedents and obstacles, to aid these discussions in the months ahead.

SUMMARY

The UK Government and EU Commission made great strides towards improving the UK-EU relations at the UK-EU Summit in May 2025. Commitments contained in the UK-EU Strategic Partnership were welcomed across the business community and cautiously by the British public. Of particular importance, both politically, and practically, is the commitment to negotiate a Youth Experience Scheme - something that Best for Britain and the UK Trade and Business Commission have been championing since suggesting the policy in 2023.

Politically, a Youth Experience Scheme is the symbol of the thawing UK-EU relations after the fraught Brexit years of the previous decade. In the EU, it is a litmus test of the UK’s trustworthiness, and its successful negotiation holds the keys to unlocking many other areas of the UK-EU trading relationship.

It is therefore unsurprising perhaps, that the EU’s outline of the scheme shows they are seeking to set new precedents, with many elements of their demands surpassing EU member states’ schemes in both ambition and scope.

In practice, the scheme will provide huge opportunities for young people in both the UK and EU, allowing future applicants to live, work and study in either country for a limited period of time. In the UK however, the Youth Experience Scheme negotiations will span a number of domestically sensitive policy areas, and all the big decisions and compromises it entails lie ahead.

The UK Government and EU commission seem far apart on whether the scheme should be capped in the first place, yet alone on what an agreeable cap could be and how it would work. Where the EU is pushing for no caps at all, immigration has surged to become the biggest issue facing the UK in opinion polls. While it seeks internal agreement on the cap in numbers, the UK Government is pointing at the precedents set by the UK’s 13 existing Youth Mobility Schemes as a guide.

While the UK’s existing Youth Mobility Schemes have been reducing net migration to the UK in recent years, migration flows are notoriously difficult to predict. Both agreement on a cap in numbers, and details of the deal will define whether the scheme is a policy success for future beneficiaries, and a political success for the government.

Agreement on the maximum duration of stay will be equally important, and the debate is likely to suffer from the same tensions as the arguments around the cap in numbers. The EU is pushing for the longest duration possible - citing four years as an example - when most of France's and Germany’s existing schemes are limited to one year.

In the UK, despite polling consistently well in principle (60% and above), support for the youth experience scheme drops by 10% if it lasts longer than two years. Though support remains above 50% even for a four-year scheme, polling suggests that a scheme lasting longer than two years could come at the expense of the support of some key groups in the UK Government's electoral coalition.

Furthermore, the Youth Experience Scheme cannot be considered in isolation to university tuition fees, and its impact on the UK’s struggling higher education sector more broadly. A scheme which allows EU students to be charged home fees, as is the EU’s ambition, would likely reverse the dwindling numbers of EU students studying in the UK. At the same time, it could exacerbate the financial struggles of some universities, or at worse displace some British students.

Continuing to charge EU students international fees, as has been the case since Brexit, would avoid setting new precedents at a time when the UK Government is negotiating with multiple trade partners, and might improve the finances of a number of struggling UK universities. On the other hand, prohibitive tuition fees will continue the downward trend in EU students coming to the UK, further reducing the UK’s soft power and standing on the world stage - especially with eastern EU member states.

The UK’s reassociation to Erasmus+ will broaden the horizons and opportunities of many young Brits and will help reverse the downward trend in EU students studying in UK universities. At a time when the UK’s public purse is under significant strain, the size of the financial contributions the UK will need to agree to could reduce the scope of the UK’s participation significantly.

Forthcoming negotiations on eligibility criteria will also be of huge consequence to the scheme's impact on net migration, and how widely the opportunities are spread across the UK. Under current measures, the total financial requirements placed on participants in UK and EU member state youth mobility schemes can exceed £3,000 in either direction - far beyond the means of the many young people in the UK.

Higher application fees, savings requirements and health insurance policies will act as a disincentive to prospective applicants, reducing the scheme’s contribution to the UK’s and EU’s immigration figures. At the same time, higher financial requirements will lock young people from lower income backgrounds out of the scheme. The UK Government and EU will have to balance competing priorities, and make difficult compromises, to ensure the scheme doesn't end up being the preserve of the privileged.

All in all, the government will have to assess the benefits and drawbacks of each of the EU’s proposals individually, and together at the same time. It will also have to balance any decisions on the welcome commitment to a Youth Experience Scheme in the context of parallel negotiations on food and drink regulations, energy security, and defence cooperation with the EU, while battling the hostile financial and political headwinds of the UK’s domestic politics.

It is a tall order, but seizing the good will on both sides of the Channel, the successful negotiation of a UK-EU Youth Experience Scheme will sow the seeds of a new chapter in UK-EU relations, with future generations of British and EU citizens reaping the benefits for generations to come.

ON CAPPING NUMBERS AND NET MIGRATION

The first major decision facing the UK Government will be its opening gambit on the ‘cap in numbers’ - the number of Youth Experience Scheme (YES) visas to be issued each year, both in total and for individual member states. The Common Understanding makes no reference to a cap or quota, and instead only references that the proposed YES should be “balanced”, and “ensure that the overall number of participants is acceptable to both sides”.

The notion of a ‘cap’, in relation to the UK-EU YES, mainly exists in the UK Government’s UK-EU Summit explanatory notes, which reference that a scheme “should be in line with the UK’s existing schemes” (which are capped), and in Ministerial public statements since the UK-EU Summit. The quotas of the UK’s 13 existing Youth Mobility Visa (YMS) Schemes vary significantly and are allocated every year, as detailed below.

Conversely, the EU negotiating mandate states clearly that “The envisaged agreement on youth mobility should be guided by the following parameters: [...] Mobility is not subject to quota”. Although the proposed UK-EU YES scheme will be the first of its kind for the EU, member states have numerous bilateral YMS schemes (often called “working holiday” schemes) in place with third countries. For example, both Germany and France have bilateral schemes in place with Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, South Korea, Japan, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Uruguay. France has additional schemes with Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru and Russia. Germany has an additional bilateral scheme with Israel.

Although information is not always readily available, it is clear that many of France’s and some of Germany’s working holiday visa programs are also subject to annual quotas. France’s working holiday visa program includes both capped and uncapped schemes, depending on the country. France’s working holiday programmes with Australia and New Zealand are uncapped. The caps of each of France’s remaining working holiday programmes are listed in Table 2.

Details of Germany’s annual working holiday quotas are harder to come by, however, Germany appears to issue a capped number of annual visas for Brazil (1,000 visas), Hong Kong (300 visas) and Taiwan (500 visas). Canada’s working holiday application website suggests that there is a quota of 3,490 visas for Canadians wishing to live in Germany for the 2025 season.

Predicting migration flows is notoriously difficult, and the relative popularity of a UK-EU YES among eligible UK and EU citizens will be equally complicated to predict. Push and pull factors will vary nation to nation and the level of agreed financial disincentives (including any restrictions on working in particular jobs) will also have a significant impact on the number of applicants either way. The Migration Advisory Committee’s (MAC) analysis of the UK’s existing YMS schemes suggests that around 10% of Australian, Canadian and New Zealanders (the main UK YMS nationals) who entered the UK on a YMS visa in the 2010s stayed longer term than their original YMS visa duration. The MAC concluded that “...the impact of youth mobility schemes on net migration in the long term will not be zero. However, it is likely to be relatively small compared to other migration categories where people have a direct path to permanent status and a higher proportion of people stay”.

When it comes to the UK’s existing YMS schemes, it is clear that they have been reducing net migration to the UK in the short term. In 2024, the UK granted 24,400 YMS visas, under a third (30%) of the total number of visas available across all UK YMSs. Over the same period, 68,495 UK citizens are estimated to have emigrated to Australia, New Zealand and Canada under the UK’s YMS visa programmes. Without accounting for the number of UK citizens moving abroad across the UK’s remaining 10 YMS programmes over the same period, the UK YMS had an effect of reducing UK net migration by over 44,000 in 2024. This pattern was repeated the year before, in 2023, when 23,000 people came to the UK across all the UK’s YMS schemes. During the same period, 34,000 UK citizens left the UK for Australia and New Zealand alone.

DURATION OF STAY

The UK Government and EU Commission will also need to come to an agreement on the maximum permissible duration of stay, and whether any provisions for extending the scheme should be included.

The Common Understanding simply states that the future UK-EU YES should apply “for a limited period of time”. The UK Government's explanatory notes further reference that the scheme will be “time limited” and “in line with the UK’s existing schemes”.

The EU’s negotiating mandate states that the envisaged YES should be “...guided by the following parameters: [...] The period of stay is limited to a reasonable timeframe (e.g. 4 years)”. Furthermore, the mandate also characterises the UK’s existing visa paths as ‘limited’ including due to their “short time limitations”.

Under the UK’s 13 current YMS visa paths listed in Table 1, the maximum permissible duration is limited to two years. However, YMS holders from Australia, Canada and New Zealand are able to extend their YMS visas for one year, once.

In contrast, France’s existing bilateral working holiday visa paths are limited to one year only, with no possibility of securing an extension. The only exception to this rule is France’s working holiday scheme with Canada, which can be extended by a further year, once.

Similarly, Germany’s working holiday programmes limit the duration of stay to one year only. Canada is once again the exception, with Canadian working holiday visa holders being granted the ability to apply for a second working holiday visa, extending their duration of stay by one year only.

Support for a UK-EU YES has polled consistently well in recent years. Best for Britain polled the proposed YMS in May 2023, March 2024, December 2024 and May 2025. ABTA and SBIT polled the YMS in August 2025. The consistent popularity of the proposed YMS is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Support for a youth mobility scheme among GB adults, 2023-2025

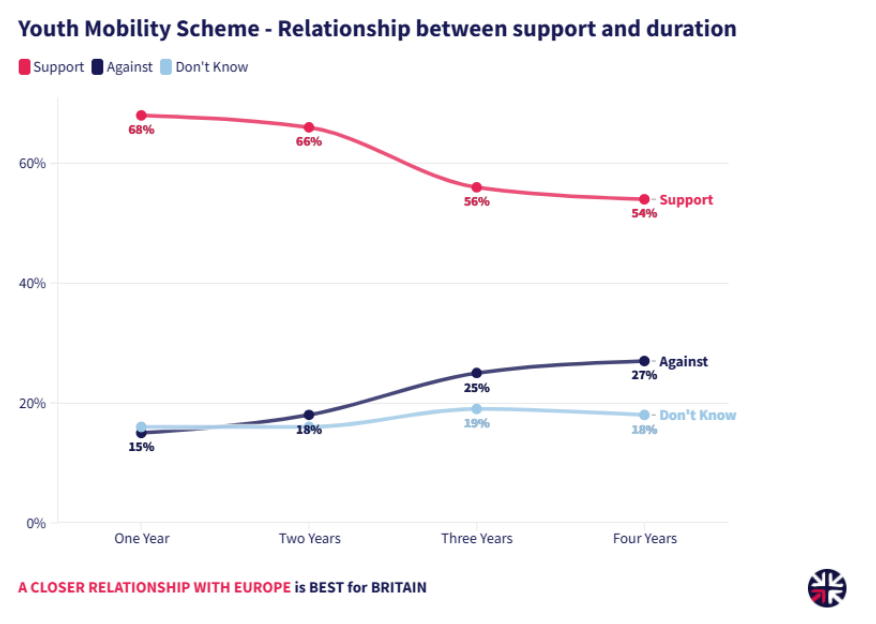

Best for Britain’s MRP poll of 15,000 respondents from December 2024 also explored how support for a YMS changed with YMS duration.

Figure 2: The relationship between YMS support and YMS duration, December 2024

The MRP estimated that irrespective of the duration of the YMS, the policy would be supported in every GB constituency. As shown in Figure 2 however, results indicated that support for a YMS reduced significantly for durations longer than 2 years. A two-year YMS was supported by 66% or respondents, dropping to 56% for a three-year YMS, and 54% for a four-year YMS.

Politically, a YMS scheme of any duration is strongly supported by Labour, Liberal Democrat and Green Party supporters. The reduction in YMS support for schemes lasting longer than two years is driven by Conservative and Reform UK supporters. A Two-year YMS carries majority support from Conservative supporters (57% in favour) and Con-Lab switchers (67% in favour), but divides Reform UK supporters (40% in favour and 46% against).

In contrast, a four- year YMS is opposed by Reform UK supporters (59% against) and divides Conservatives (44% against, 40% in favour). Crucially, a four-year YMS divides Con-Lab switchers, with 39% against and 49% in favour.

UNIVERSITY TUITION FEES

It is clear the EU sees the proposed UK-EU YES as a new avenue for EU students to access UK universities and higher education institutions. It may even see it as a vehicle to replace the UK’s existing student visa route for prospective EU students. The EU’s negotiation mandate states that the UK-EU YES should provide a “clear, simple and cost-effective path for mobility” which would also “address the main hurdles for young Union citizens (e.g. in respect of education tuition fees or of work placements as part of Union studies) which other options (such as the United Kingdom Youth Mobility Scheme) do not address”.

However, the EU’s negotiation mandate also states that they are seeking that “Equal treatment is also provided in respect of tuition fees for higher education”. That is to say that EU citizens should be charged the domestic rate of university tuition (capped at £9,535/year for undergraduates in England and Wales) which, if granted, would be a unique concession to EU students. Furthermore, the EU is seeking that this exception be applied to “beneficiaries of other visa paths” - EU citizens studying in the UK under the UK’s student visa scheme.

The commitment to negotiate a UK-EU YES cannot therefore be considered in isolation to higher education tuition and, with the UK higher education sector facing a well documented and mounting financial crisis, the UK Government’s position on tuition fees for EU students will have a profound impact on the UK higher education system more broadly.

Under current arrangements, non-UK citizens are eligible to pay home fees if they have settled status on the first day of the academic year. This means that under current agreements, most EU citizens applying to come to a UK university under a future UK-EU YES are liable to be charged international fees, which are not capped and are set by the education provider.

It also means they will not be eligible for student loans, something the EU negotiation mandate clearly states is not being pursued by EU negotiators: “The treatment of beneficiaries of the envisaged agreement should be equal to nationals, [...]. It should not extend to study and maintenance grants and loans or other grants and loans”.

It is likely that the EU’s demand for EU students being eligible for home fees in the UK is borne from both the un-capped nature of international tuition fees in the UK, and the significantly higher tuition fees in the UK compared to EU member states, where higher education is heavily subsidised. In France for example, domestic undergraduate tuition fees at a public university are around €170/year, and €2,770/year for international students (tuition is however comparable for some of France’s grand écoles, which can charge around £9,000). In Germany, tuition is free for both domestic and international undergraduates, with the exception of the Baden-Wuttenberg area. There is also believed to be a personal dimension, in that the families of those in European institutions are affected.

The impact of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), and change in tuition fees chargeable to EU students, has had a significant impact on the number of EU students coming to the UK. In 2021, when the TCA came into effect, applications from EU students to UK universities dropped by 40%. Although the TCA’s implementation coincided with the lockdowns and travel restrictions resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, in 2024, the number of EU students on full-time undergraduate courses had fallen by 68% compared to 2020 - its lowest level since 1994. Despite the compounding effects of Covid-19 pandemic, it is clear that higher tuition fees caused the number of EU students in the UK to crash, and they have so far not recovered.

When it comes to the type of degree EU students are obtaining in the UK, EU students are outliers compared to non-EU international students. For the 2023/2024 academic year, 63% of EU students at UK universities were in first-time undergraduate courses, compared to only 35% of non-EU international students who were doing the same.

It is therefore possible that a reversion to charging EU students UK home fees, as was the case before the TCA was implemented, could help the number of applications from EU students in the UK to recover. However, if the annual cap of £9,535 on home tuition fees causes UK universities to make a financial loss on tuition, then increasing the number of university places available to accommodate the increase in the number of students enrolling on home fees could accelerate the financial crisis of UK universities. Alternatively, if universities were to not increase the number of places available to accommodate the new influx of EU students, the result could be EU students “displacing British students”.

When it comes to tuition fees, the first consideration for the UK Government should be whether to set a new precedent by allowing EU citizens to pay home fees, and how such a precedent may impact ongoing and future trade negotiations with other countries. The UK Government currently has open negotiations with the US, Gulf Cooperation Council, Switzerland, Turkey and South Korea, and with China. The UK Government trade strategy further outlines the UK Government’s ambition to negotiate Digital Trade Agreements with Brazil, Thailand, Kenya and Malaysia.

The question of tuition fees is further complicated by the interpretation of ‘home fees’ as applied to universities in Scotland and Northern Ireland, where home fees are lower than in England and Wales. Taken at face value, the EU’s demand for ‘equal treatment to nationals’ could result in future EU undergraduate students being charged the lower £1,820 home fees for Scottish citizens in Scottish universities and £4,855 in universities in Northern Ireland, with English and Welsh citizens paying the higher (£9,535/year) ‘Rest of the UK’ fees.

The most important question for the UK Government however, will be how the UK-EU YES will impact the UK’s struggling higher education sector. A UK-EU YES which agrees to allow EU students to be charged home fees would bring the welcome benefit of reversing the downward trend in the number of EU students choosing to come to study in the UK. At the same time however, it could exacerbate the mounting financial crisis in the UK’s higher education sector, or come at the expense of the number of university places available to UK students. Continuing to charge EU students international fees, as is the case now and the case with students from all other countries across the globe, will have the effect of not setting new precedents and not adding to the financial woes of UK universities. At the same time however, it would likely continue to drive the downward trend in the number of EU students coming to the UK to obtain a degree, and further reduce the UK’s soft power and standing on the world stage.

FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS AND OTHER PROVISIONS

The UK Government and EU will have to agree on the YES fee costs, with the EU’s negotiating mandate stating that “Fees for handling the applications or issuing a visa or residence permit should not be disproportionate or excessive”. The UK’s existing YMS fees stand at £319, while France’s and Germany’s working holiday handling fees are comparatively less expensive, at €99(around £88) and €75(around £65) respectively.

The UK’s YMS visa fees are less expensive than the UK’s international student visa fees, which currently cost £524.

An agreement will have to be reached on how YES participants access the host country’s health service. The UK’s current YMS schemes require successful applicants to pay a £776 health surcharge for every year of their stay. This also applies to all international students residing in the UK on a student visa, though EU students are able to claim a refund, provided they have a European Health Insurance Card.

European countries also have special requirements for accessing their countries’ health services, with working holiday visa holders in both France and Germany requiring applicants to obtain private medical insurance worth up to €30,000, covering all medical eventualities. UK citizens are able to avoid obtaining such medical insurance, provided they have obtained a UK Global Health Insurance Card (GHIC).

Both the surcharge and insurance models will have benefits and drawbacks, but the EU has given a clear indication of wanting to apply the EU insurance-based system, stating in its negotiation mandate that the “envisaged agreement should waive, for Union beneficiaries, the United Kingdom healthcare surcharge” and separately, that conditions for admission should include “e.g. [...] a valid comprehensive sickness insurance”.

Both the UK and EU require proof of significant savings from prospective YMS/working holiday visa applicants. In the UK, YMS applicants are required to demonstrate a minimum of £2,530 in savings. France’s proof of funds rules are comparable, with YMS applicants required to show they have €1,700-€3,100 (£1,470-£2,680) in savings, depending on the country of origin. Similarly, Germany requires YMS applicants to demonstrate €3,000 (£2,600) in savings and proof of a €1,000 (£866) monthly income.

Under current measures, the total financial requirements can exceed £3,000 in either direction. Higher application fees, savings requirements and health surcharges/health insurance policies will act as a disincentive to prospective applicants, reducing the YES’s contribution to the UK’s and EU’s immigration figures. At the same time, higher financial requirements will disincentivise young people on lower incomes and from lower income backgrounds first, making the scheme less equitable and more elitist. The UK Government and EU will have to decide if the priority is controlling the number of applicants, or making the scheme as equitable as possible, or both.

The EU’s negotiation mandate also stipulates that any future UK-EU YES agreement should “not allow for “intra-Union” mobility to another Member State”, meaning that future UK YES applicants would be able to reside in one EU country for the duration of their visa. Given the EU negotiation mandate makes no reference to Schengen visa rules, it will be important the UK Government ensures that future UK YES holders will, at the very least, be able to travel to other EU member states under 90/180 Schengen visa rules, in-line with EU member states’ existing working holiday visa programmes.

The EU is also seeking an agreement on the “conditions for the exercise of the right to family reunification”, something which neither the UK’s nor EU member states’ existing working holiday visa schemes make provisions for. The UK Government’s explanatory notes clearly diverge from the EU’s negotiation mandate, stating: “but the UK has been clear that any scheme should be in line with the UK’s existing schemes including participants having no access to benefits and no right to bring dependents”.

The UK Government will have to consider the EU ask for family reunification rights, in the context of having reversed the right to bring family dependents under its other visa routes, including international students, as recently as January 2024. The UK Government also suspended the right to family reunification for asylum seekers, from September 2025.

ERASMUS+

In the Common Understanding, the UK and EU committed to “work towards the association of the United Kingdom to the European Union Erasmus+ programme”. The details of the terms of association are still under discussion, and are likely to focus on the “fair balance" between the UK’s financial contributions to the scheme, and the “benefits to the United Kingdom”.

The UK Government’s explanatory notes go further, detailing that negotiations on Erasmus+ are taking place “on the clear mutual understanding that the UK will only associate to Erasmus+ on significantly improved financial terms”.

The EU’s enthusiasm for the UK to reengage with Erasmus+ is driven by the same reason causing the UK Government’s caution. In 2018, 29,797 EU students came to the UK through Erasmus+, 64% more than the number of UK students going the other way. The value of Erasmus+ projects in the UK in 2018 was €145million (around £127million). For the same time period, Boris Johnson’s government estimated the proportion of the UK’s contribution to the EU budget allocated to Erasmus+ to be £241million.